Wednesday, September 07, 2005

Observers are Information

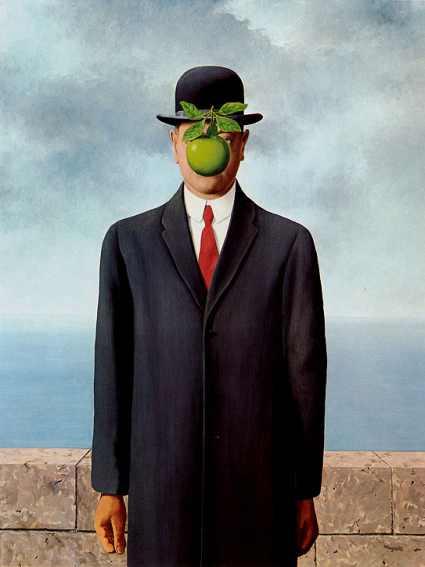

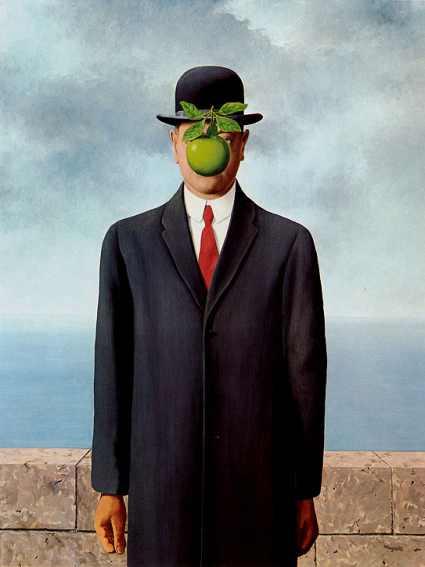

In the previous 2 posts I argued that the ensemble (the collection of all mathematical structures) exists, and that observers form the largest class of information in the ensemble - which explains why we are observers. However, it might not be obvious at first that an explanation is needed for why existence entails being an observer, so it is important to emphasize the nature of the problem. The key is that any moment of consciousness is just another type of information, no more and no less. For instance, at any moment in time some subset of the neurons in an awake persons' brain will be firing, and it is the abstract connected graph formed out of those active neurons that is equivalent to that person's conscious experience. That is, the vast connected graph formed from the interacting neurons actually is the conscious experience.

There is a significant caveat to this - in fact only a subset of the patterns formed by the firing neurons will be equivalent to the conscious experience, as many of the other areas of the brain are responsible for the preprocessing of the information that the conscious areas then utilize. For instance, Christof Koch argues that the V1 area in the visual cortex is not the seat of conscious perception, but rather collects, organizes, and refines the information coming in from the retina for use by subsequent areas like the Medial Temporal Lobe.

There is still an intuitive disconnect towards idea that specific abstract connected graphs could be equivalent to mental experiences such as the sensation of color. This is the hard problem from the philosophy of consciousness, and it is likely that we won't have a completely satisfying answer until we understand in depth how the experiences arise from the interactions of the neurons. However, I have come up with a simple counterargument to the reflexive disbelief that the topologies for firing neurons could be equivalent to the subjective experiences of various qualia. The key is to again consider the mind as a giant connected graph. This giant graph is comparing to small subsets of itself: one, the self-referential idea of connected graphs, and two, some particular sensory perception (say the vivid orange color of a carrot), and, not surprisingly, finding that they don't "feel" the same. Nor should they - the two areas of the brain will be connected in very different ways, and we don't have any direct access to all the unconscious subroutines in the brain that provide our consciousness with high level abstract data. If the human brain had the ability to directly observe the status and connectivity of its own neurons, then there would likely be a lot less mystery to the subject. And its not surprising that it doesn't - it would require a lot more neural hardware for such introspection, and there may be no simple path for such hardware to evolve, or a compelling biological pressure for it to do so. However, it will be available for advanced artificial intelligences in the decades to come, who will thus be able to understand themselves at a much deeper level, as well as having a means to develop all sorts of intriguing enhancements to their consciousness.

So our various conscious experiences as observers of a complex exterior reality are nothing more than particular types of information. There is nothing intrinsically special about them, no essence of vitality that breathes life into them. And all other things that exist (like universes and mathematical structures and so on) are just particular forms of information as well. Thus the quandary is now thrown into high relief: why does existence entail being a member of the class of information that describes observers? And the Observer Class Hypothesis answers: because there are categorically more observers than any other type of information, since observers can observe and subsume any other type of structure. And the OCH predicts that there is no upper bound to the complexity of information that we will eventually be able to absorb - a rather audacious bet. The longer that we can continue to upgrade the power of our brains, thus allowing us to think exponentially more diverse thoughts, then the greater confidence we can have that the OCH is correct, and the better we will understand why we exist. If the OCH is correct, then the journey will always be just beginning.

There is a significant caveat to this - in fact only a subset of the patterns formed by the firing neurons will be equivalent to the conscious experience, as many of the other areas of the brain are responsible for the preprocessing of the information that the conscious areas then utilize. For instance, Christof Koch argues that the V1 area in the visual cortex is not the seat of conscious perception, but rather collects, organizes, and refines the information coming in from the retina for use by subsequent areas like the Medial Temporal Lobe.

There is still an intuitive disconnect towards idea that specific abstract connected graphs could be equivalent to mental experiences such as the sensation of color. This is the hard problem from the philosophy of consciousness, and it is likely that we won't have a completely satisfying answer until we understand in depth how the experiences arise from the interactions of the neurons. However, I have come up with a simple counterargument to the reflexive disbelief that the topologies for firing neurons could be equivalent to the subjective experiences of various qualia. The key is to again consider the mind as a giant connected graph. This giant graph is comparing to small subsets of itself: one, the self-referential idea of connected graphs, and two, some particular sensory perception (say the vivid orange color of a carrot), and, not surprisingly, finding that they don't "feel" the same. Nor should they - the two areas of the brain will be connected in very different ways, and we don't have any direct access to all the unconscious subroutines in the brain that provide our consciousness with high level abstract data. If the human brain had the ability to directly observe the status and connectivity of its own neurons, then there would likely be a lot less mystery to the subject. And its not surprising that it doesn't - it would require a lot more neural hardware for such introspection, and there may be no simple path for such hardware to evolve, or a compelling biological pressure for it to do so. However, it will be available for advanced artificial intelligences in the decades to come, who will thus be able to understand themselves at a much deeper level, as well as having a means to develop all sorts of intriguing enhancements to their consciousness.

So our various conscious experiences as observers of a complex exterior reality are nothing more than particular types of information. There is nothing intrinsically special about them, no essence of vitality that breathes life into them. And all other things that exist (like universes and mathematical structures and so on) are just particular forms of information as well. Thus the quandary is now thrown into high relief: why does existence entail being a member of the class of information that describes observers? And the Observer Class Hypothesis answers: because there are categorically more observers than any other type of information, since observers can observe and subsume any other type of structure. And the OCH predicts that there is no upper bound to the complexity of information that we will eventually be able to absorb - a rather audacious bet. The longer that we can continue to upgrade the power of our brains, thus allowing us to think exponentially more diverse thoughts, then the greater confidence we can have that the OCH is correct, and the better we will understand why we exist. If the OCH is correct, then the journey will always be just beginning.